What Is Iaijutsu and Iaido?

The word iai 居合 contains the idea of meeting an opponent that is attacking you. There is a slightly defensive nuance to this word. Iaijutsu and iaidō arts start with the sword in the saya (sheath). Alternatively, the art of drawing the sword is called Battōdō 抜刀道 or Battōjutsu 抜刀術. Battō is pulling out the sword from the saya. In iaijutsu the techniques are centered around responding to an agression while your sword is in its saya, or deploying the sword to act agressively. There are some common main components to iaijutsu such as nukitsuke, kiriotoshi, chiburi and nōtō.

Components of Iaijutsu

Nukitsuke

The first major component of Iaijutsu is the drawing or deployment of the sword. This is some times done as a draw and cut with one motion. This is what nukitsuke refers to. However, not all first motions with the sword are used to cut. Every school has different methods of drawing and utlizing the sword once deployed fully from the saya.

Furikaburi

There is a minor component of Iaijutsu that sometimes follows the initial draw or deployment. This movement is usually referred to as furikaburi. This motion brings the sword around the head to begin the next or final cut. Some techniques do not use this. It can often be missing from many waza. I label this is a minor component.

Kiriotoshi

The second major iaido component is kiriotoshi or kiritsuke. Usually, after the sword is deployed, there is a significant strike that is considered the final blow. This is not always the last strike of a form, however. Kiriotoshi is sometimes referred to as kirioroshi. Kiriotoshi means drop-cut. These cuts are some of the most potent cuts in swordsmanship. Some schools have entirely different methodologies of their kiriotoshi. In Shinkan-ryū Kenpō the kiriotoshi has subtle aspects that are important to its practices.

Kiritsuke

The second part of the second major iaido component is kiritsuke. After nukitsuke, there might follow a strike with the sword that is not a final drop cut. It can likewise be a series of strikes. These are generally referred to as kiritsuke. It means cutting/slashing. Iaido and Iaijutsu typically feature either kiriotoshi or kiritsuke. Many techniques have both.

Chiburi

The third iaido component is chiburi. After all the striking is done, before returning the sword the act of chiburi is completed. Chiburi is the symbolic shaking off of the blood from the sword. This is done in a myriad of ways. Many schools throughout history used different methods. The primary purpose of this act was for training in general. Some schools do not have actual movements to remove the blood but instead have the same moments of mental focus (zanshin) that remain after the attack has been completed. Some schools make use of a tissue or cloth, or even their shoulder or hakama to remove the blood in place of the act of chiburi (shaking of blood).

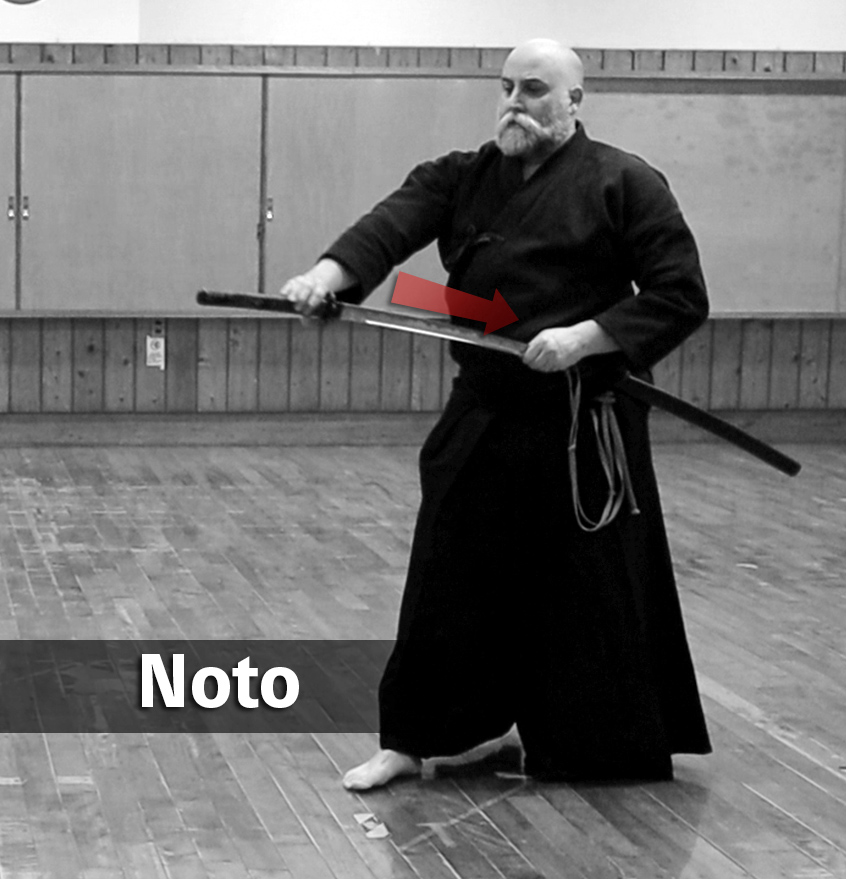

Nōtō

The fourth and final iaido component is nōtō. After chiburi is completed, the sword is returned to the saya. There are many styles to noto as well. Nōtō is a time to keep and not lose concentration as it does not mark the end of an engagement.

What is the difference between iaidō and iaijutsu?

The art of iaijutsu is commonly known around the world as iaidō. The art of drawing the sword is known by many names, iaijutsu, battojutsu, bakken, and nukiai. The question often asked is are iaido and iaijutsu the same? Iaidō and Iaijutsu refer to the art of drawing the sword in attack or defense. The first difference to note is the semantic differences between dō and jutsu. Dō or michi 道 has the connotation of character refinement and spiritual training. In arts that use dō as their suffix, the main ideas are character refinement and aesthetics and generally not combative aspects. Jutsu 術 means art or technique. The styles usually using jutsu as their suffix are more some times more concerned with combat effectiveness as their goal.

The difference between dō and jutsu can be seen as semantics. People sometimes argue that Japanese themselves do not make a distinction over something like Judo or Iaido having decent martial applications. The changes in names from Jujutsu to Judo, however, do have some ramifications in the way the art was developed beyond its original intent as a dependable battlefield or warrior skill.

The dō systems are sometimes erroneously looked at as inferior to the jutsu forms. Kendō while limited in its teachings for sword combat does have its own place in the spectrum of sword arts from Japan. It is not helpful to dismiss such a school as not worthy of swordsmanship training. Do not let the dō suffix always fool you into thinking the techniques are subpar. As well jutsu schools can also contain strong points of spiritual refinement and character development. So this idea between the difference of dō and jutsu can be a little complicated as you can see.

If you are thinking, well this is a slippery slope to climb, it is indeed. You have to keep an open mind and not judge a book by its suffix. Japanese do use these words interchangeably as well. It can be said its just semantics but its foolish to think that is the only case.

Shinkan-ryū Kenpō's iaijutsu is concerned less with looking perfect and is more intent on being true to its original nature of sword fighting methods. In Shinkan-ryū Kenpō there are many forms and levels of interesting iaijutsu techniques.