Practicing and Studying

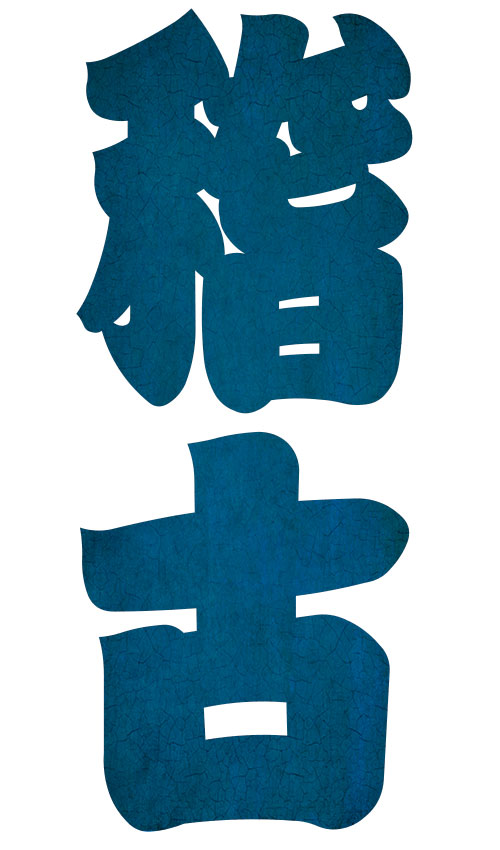

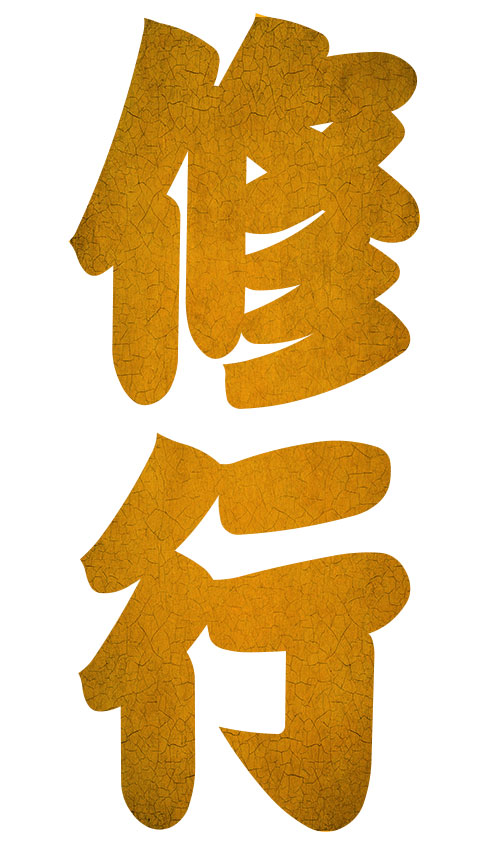

There are two main words used about practicing and learning in martial arts. Generally, we wouldn't say, I do martial arts, but rather that we practice martial arts. I want to talk the words, Keiko 稽古, and Shugyō 修行. There are a few more words to describe doing and learning, but I feel keiko and Shugyō are the main ones to examine.

When I was young, I recall seeing movies where the martial arts master stood under a waterfall in the icy winter morning, focused and breathing deeply while cold waters fell upon his lean powerful figure, performing seemingly simple movements of his arms. Concentrated and dedicated in his art. I thought, "Wow! That's some intense training." Now that was exciting to see as an 11-year-old. Cinematically you can’t beat those types of scenes depicting martial arts practice.

Even sitting under a tree and profoundly meditating. We can imagine the grand visions or the flashbacks to get these ah-ha type moments. Then there’s the warrior training with his sensei or senior members. Sweating, grunting and performing techniques over and over until he ‘gets it’. Or other shugyō training montages showing his progress from inept to adept. He used to trip over that rake. Well, now he and that rake are one. Look out bad guys, or un-neatly piled autumn leaves!

Are all the comic books and movies, and even in-dojo stories about shugyō and deep austere practices correct? We have these two ideas and words, Keiko 稽古, and Shugyo 修行. I would like to break down and examine these words for a clear understanding.

Contemplating What Came Before

We shouldn't just do martial arts; we should contemplate them deeply. Keiko 稽古 has two kanji, the first meaning ‘to think or to consider’. Kei 稽 is also known as kangaeru 考える. The second, ko 古 means old. Yes, that's the same ko as in koryū 古流, kobudō 古武道 or kobujutsu 古武術. We can even use keiko when we talk about our violin practice. Our martial arts attire is also referred to as a keikogi 稽古着, keiko to contemplate the past and gi 着 meaning something worn.

When we perform keiko, we are refining and considering the things that came before us; the teachings. We are practicing. Like learning how to write, look at the letters that were formed long ago, copy them, and repeat, repeat. In Chinese or Japanese, the characters can often be complex and have a long history. Even in something as simple as writing we can think about the origins of the letter. We are taught something that has come before us, and we copy it. Then reflect on it. We look at the past and think of what we should do. To consider what came before. This is keiko.

Walking As A Monk

Shugyo 修行 is also made up of two kanji. Shu 修 meaning ascetic practices or discipline. And gyo 行 which means journey, or to go. It can even mean conduct. Shu 修 is also derived from a Buddhist word. The Sanskrit is Sadhana. When you are skillfully applying mind and intelligence towards a spiritual goal. I guess you can already sense the connotations for using shugyo over keiko.

Shugyo for Buddhist monks (referred to as angya 行脚 ), for example, is one form of practice. It seems that before the Edo period (1603-1868) traveling and undergoing intense training was popular for bushi. Musha-shugyō is the term used for martial artists that are performing shugyō. Yamauchi Genbei was a samurai in 1542 that popularized the idea of musha shugyō 武者修行. He traveled to many kenjutsu and sōjutsu teachers to learn and increase his skill. Not only growing his abilities but it also beefed up his resumé. At the dawn of the Edo period, such activities died down a bit. At the end of the Edo period, however, during the bakumatsu period (1853-1867) it again became popular. It was from monks practices that the idea of sitting under waterfalls or training alone at a remote shrine got its foothold in the martial arts community. Some believe that it is an express line from regular keiko to some enlightenment.

Are we looking at extreme shugyo the wrong way?

Is waterfall training beneficial in this day and age?

Does participating in some intensive weekend program once a year or less benefit us? I think it is akin to visiting a one-day seminar about self-help issues. The clouds part we see the light, but then eventually we go back to daily life and things going dark again. We’ve all likely experienced this happening to ourselves or someone we know. I know that I have. These are fleeting moments that do not have the strength to uproot the fetters that are preventing us from increasing our spiritual energy.

The benefit to real shugyo is the sustained application of thought and mental energy. It is about keeping the trajectory and momentum. It's quite normal during any kind of shugyo or meditation that the mind strays. That is not a defeat. That's the time when we must bend it back towards our goal with our awareness. The point I want to make is that we don’t need to be dipping our private parts into icy waters and reciting secret passages to get some liberation or enlightenment. Those types of approaches to shugyo are not meant to break us open and fill us with the power of the universe. People often cite esoteric practices as short cuts. The results produced by such things are flimsy at best.

Where to practice shugyō?

Getting to practice amidst your daily life and its routines are shugyo as well. Pushing through the difficulties and striving for the next plateu is shugyo. Going to the dojo when you’d rather binge watch some tv show, or play with your friends. Performing sustained mental concentration through physical practice for long hours pays off in the end. It doesn't mean that all your practice needs to last for 10 hours or 2 weeks at a time, but it does benefit us to pepper in shugyo throughout our keiko. Handling difficult situations within training with people we don’t like or those that start trouble. Those are aspects of shugyo too. A constantly applied mind to these situations will get us further than a weekend of hypothermia. There are of course some benefits to pushing yourself into the uncomfortable areas. I’m not saying there’s nothing at all to be gained from that, but open your eyes wider to what shugyo and deep training are and don't be conned into short cuts or actual practices that are wastes of time.

Everyday life is our true keiko and shugyõ. Living it correctly with a mind imbued with compassion for ourselves and others. Kindness towards our mistakes and others. Concentration on our shortcomings and weakness. Admission of our own mistakes and understanding why we transgressed. Bolstering the parts of us that need strengthening and developing the wisdom to be wholesome and learn our art as correctly as we can. Constant mindfulness in and outside of the dojo is our ever-present shugyō. This meditation (mindfulness) leads to wisdom. Wisdom leads to a greater understanding of ourselves and our arts.

Serious martial artists, musicians, or anyone earnest about their crafts perform keiko or shugyo.

©2018 S.F.Radzikowski

ラジカスキー真照

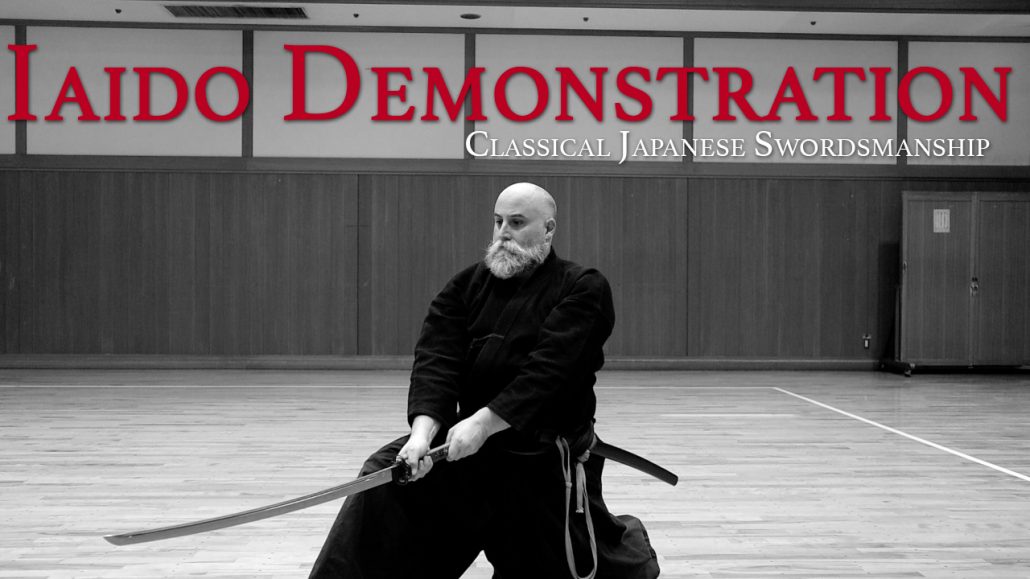

館長Saneteru Radzikowski is the head sword instructor of Shinkan-ryū Kenpō. He lives and teaches Iaijutsu and Kenjutsu from Nara, Japan.

Maai; Combative Space-timing

Teaching maai 間合い, the ideas of combative spacing and timing intervals in kenjutsu.

Covid-19 Corona Virus And Martial Arts

A Very Budo Christmas Happy Holidays & New Year

Happy Holidays and Happy New Year to all of you that were kind and supported...

Tachi Iai & Suwari Iai Demonstrations

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent="no" hundred_percent_height="no" hundred_percent_height_scroll="no" hundred_percent_height_center_content="yes" equal_height_columns="no" menu_anchor="" hide_on_mobile="small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility" status="published" publish_date="" class="" id="" background_color="" background_image="" background_position="center...

Waza: Quality or Quantity?

Waza Waza Everywhere In our respective martial arts systems, we learn many waza 技 (techniques)....

Guilt and Responsibility

I heard a student say, “If I don’t do any kind of training every day,...

The Sword With Two Edges

Today I decided to write the four kanji compound of morohanotsurugi. In English, we might...

Respect is a two way street in martial arts

Respect is a two-way street, however, how many people are driving recklessly? “If you want...

The Point of Iaido & Tame

Pardon the pun, but the point of iaido is important to keep. When we practice...

Code of Bushido Righteous Heart

Being righteous and doing the right thing is one of the foundations of body and...

Honesty and the Martial Arts Hermit. Being a good budō teacher and student.

When people want to find a martial arts teacher, do they often think of mister...

Munen Muso And Mushin The Warriors Mind

What is the difference between munen and mushin? These concepts outline the ideal mental state...

Rei – 礼 – Gratitude In Budo Training Life

Gratitude for our swords and training equipment, and those that made them. To our teachers...

6 Years of Shinkan-ryū Kenpō

Last week marked the 6th year of Shinkan-ryū Kenpō. I want to thank the faithful...

Cómo aprender Kenjutsu?

Aprender cualquier cosa tan profunda como un arte marcial requiere de un maestro. El kenjutsu,...

Attachment, Budo & Impermanence

It is worth a lot to be mindful of the ebb and flow of all...

Martial Arts and The Path: Strive for the truth

If you study the way and path 道, then you should understand the truth correctly....

A Disease of the Swordsman

The Sword and its study. Hesitation (doubt) is one of the four diseases in swordsmanship....

Sword Control

We should not let our mind or body or sword become contorted or controlled by...

Budo Don’t

Don’t be in love with your weapon. Don’t be in love with your uniform. Don’t...

How To Learn Samurai Sword Fighting Without A Teacher?

I get asked often, “Hey, is it possible to learn sword fighting without a teacher...

Shugyō and Keiko Martial Arts Practice

Practicing and Studying There are two main words used about practicing and learning in martial...