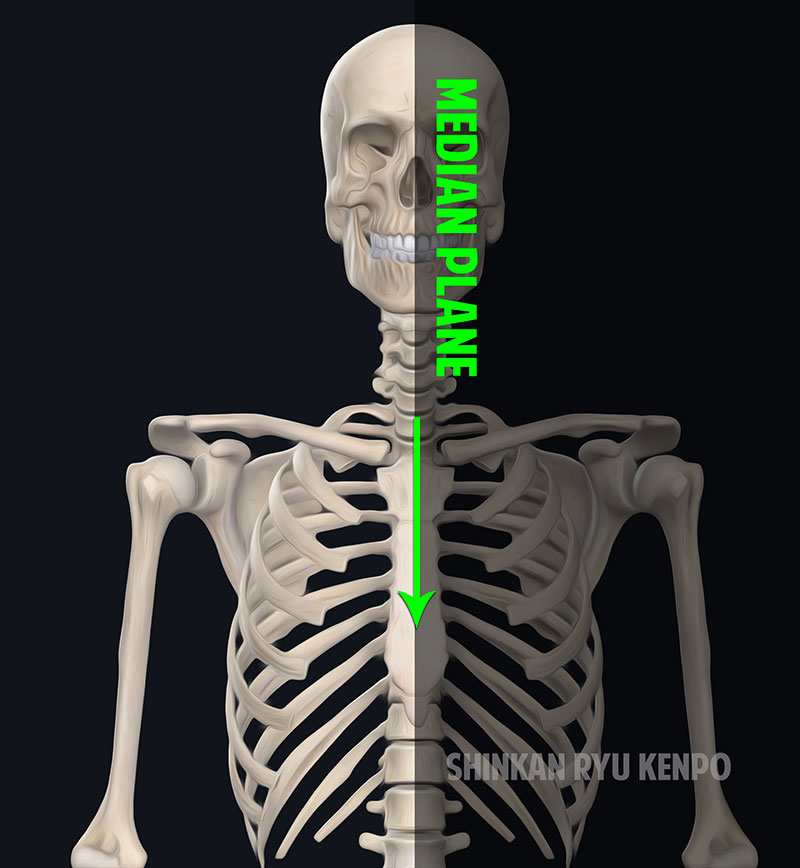

In Japanese swordsmanship, there have been many hundreds of schools. There are, however, only a few ways to cut with a sword. Many schools feature a cut coming from the top of the head straight down in a vertical manner. This cut is along the median plane which bisects the body in equal left and right parts. In iaido parlance, this overhead vertical cut is referred to as kiriotoshi, kirioroshi, and shomen-giri.

The first target that is being affected by such a cut is the skull. The one issue with this cut is that the skull is shaped in such a way that these types of cuts have a lot of variables that can cause them to fail. I use the word fail, and it sounds as if I am calling this cut non-effective. I am not saying that in an absolute way. There is a potential for such a cut to glance off the rounded structure of the skull. That is, of course, one of the reasons for the design of the skull. To protect and house the eyes, and brain. It is not always preferable to use this strike, and it seems that historically, many haven't in actual battles.

This cut is usually reserved for the final blow or coup de gras. It certainly can be fatal, but again the rounded and curved surface of the skull does make it hard for the katana to always deal a deadly strike. Even harder if the opponent has headgear. During a sword fight, chances must be taken advantage of and a myriad of strikes and techniques are used. Therefore other types of angles are also taught.

I would classify kiriotoshi and the median plane strike as practical but not always a guaranteed mortal wound due to the need for extreme precision of cut placement on the rounded surface of the human skull using a katana. A glancing blow, while very painful indeed, is not going to do the trick. There also seems to be a few real-world injuries evidenced on skeletal remains in Japan. My understanding is that this strike is an ideal cut. While still important, I find kesa-giri to be much more interesting and versatile. Many schools use kesagiri in place of the shomen-giri.

It's All About The Angles

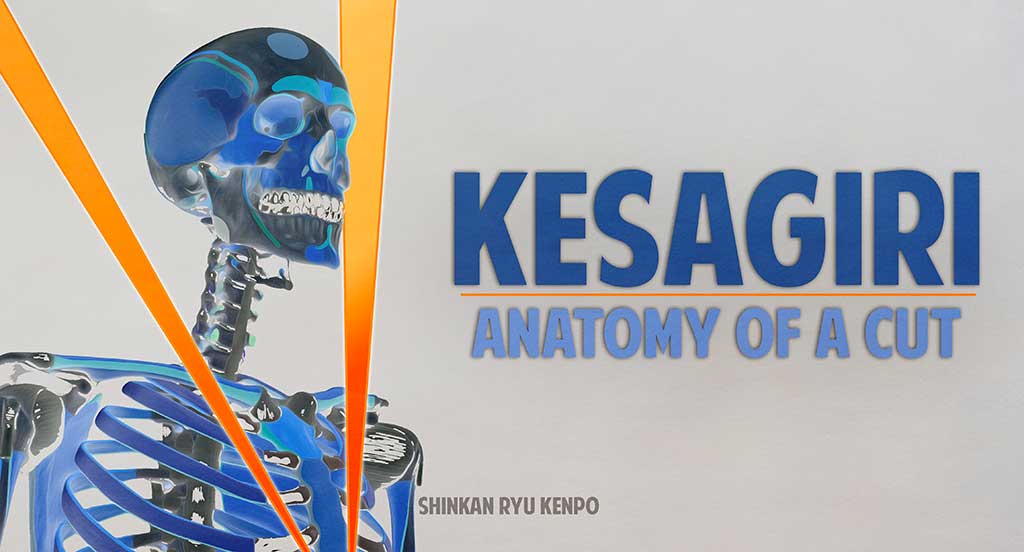

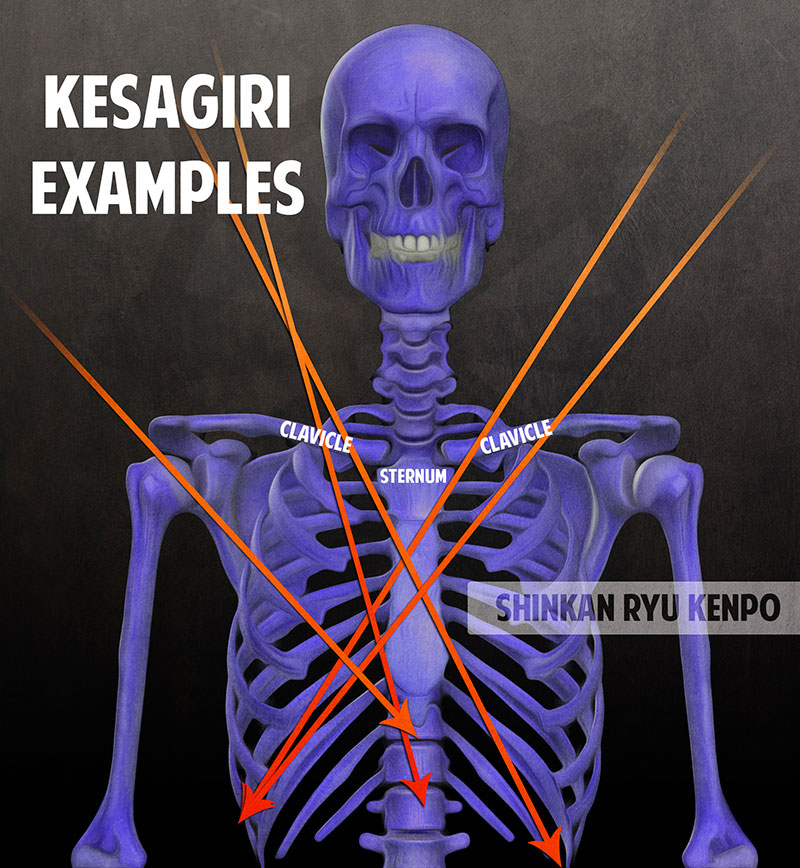

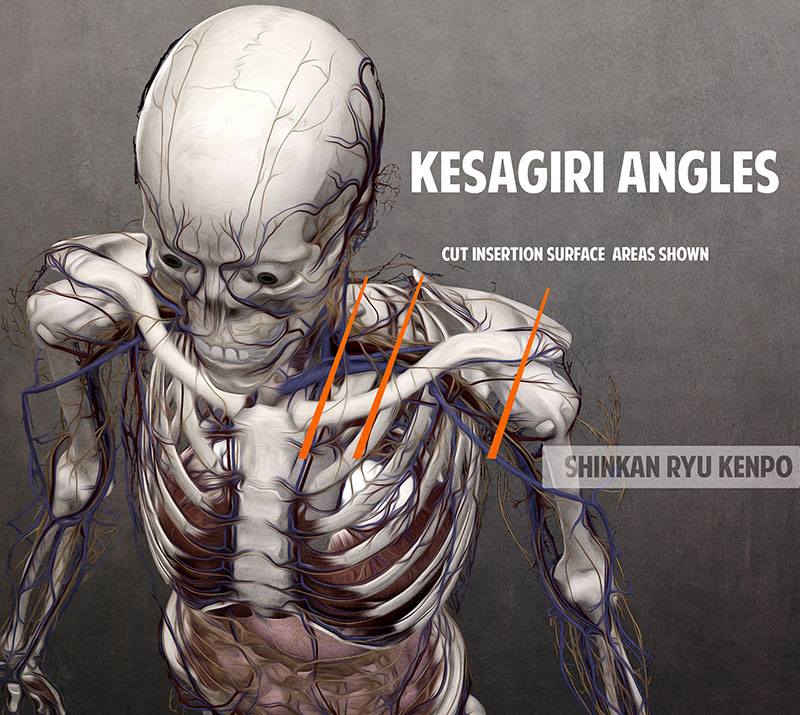

There is another cut which is diagonal in nature coming from the top; kesagiri. Kesagiri is a compound of two words. The first, kesa, is in relation to the robes that Buddhist monks wear. Giri or Kiri means to cut. Commonly seen as the robes that drape over the shoulder and it's lapel line is similar to the angle of the cut performed in kesagiri. Your keikogi has a similar V shape as well.

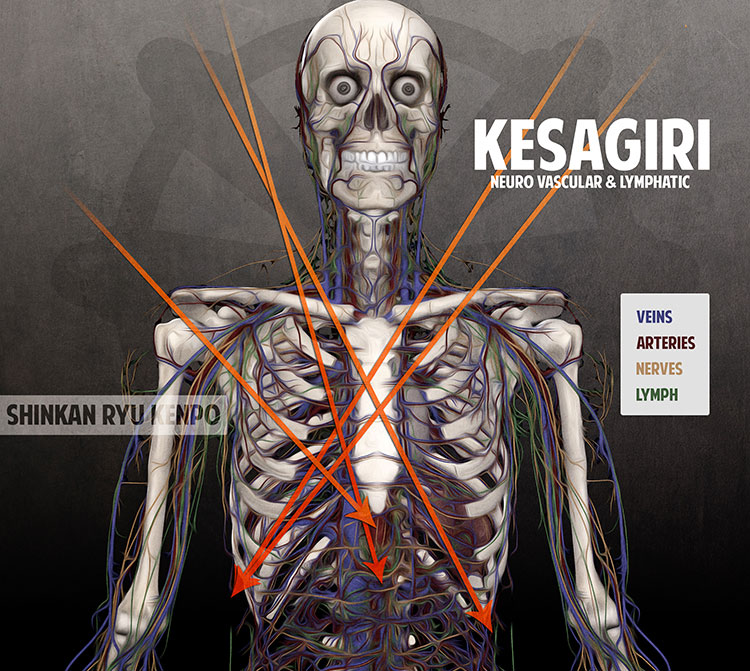

The illustration above shows various kesagiri angles that some iaido/iaijutsu schools use. This sword strike comes from the upper positions often referred to as jodan. From here the attacks come down and have different intended stopping points. Some pass through the rib cage and some stop just below the xiphoid process. It is important to note that not only the body is affected by kesagiri but also the limbs. Why is kesagiri so devastating? It might seem that it is passing many more bones than the kiriotoshi strike and cannot deal much damage. Let's take a cursory look at what's going on with kesagiri.

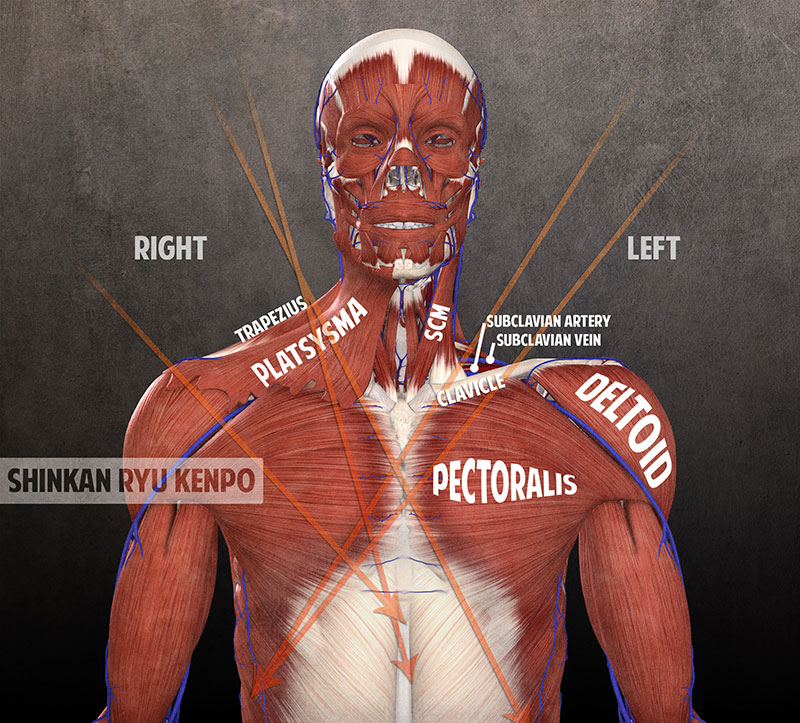

The image above shows some basic anatomy. The left side of the body has the platysma and Trapezius removed. Under that, the vascular bundle that contains the subclavian vein and artery can be better seen. This vascular bundle mainly feeds the arm and hand. Not shown in this image is the Brachial Plexus which is a nerve bundle coming from the neck also feeding the arm and hand.

Kesagiri has the sword striking the muscles of the shoulder mostly. This has a limited effect on mobility or the use of the arm. The arm could still most likely be raised somewhat and used. The real issue, however, is the severing of the neurovascular bundle just under those muscles and the clavicle.

Visualizing iaido or kenjutsu like this seems exceptionally violent. We must though, as students and teachers contemplate the actions of the sword and its consequences. I take no pleasure thinking about the details, but they must be thought about to understand what the sword art and techniques are conveying.

The sword can break through the clavicle which will make it difficult to use that arm. The sword at this point will sever the veins and arteries that are usually protected by the clavicle. The loss of blood from this area will often result in unconsciousness in a few minutes and death from the loss of blood within around 60 minutes. If the clavicle or ribs are also broken the likelihood of further complications occurs as bone fragments can rupture the veins there. This is a problem if only the ribs and clavicles are broken while surviving the initial sword strike.

It seems rather good odds that the sword will reach the brachial plexus which will sever the nerves to the arm, as well as the subclavian artery and vein causing a traumatic shock (unconsciousness) and blood loss.

If the sword can continue further down through some of the various angles of kesagiri then it will intersect with the heart just behind the sternum.

Kesagiri, as with all sword strikes is a lethal experience. Walking away from even glancing blows to the head has a myriad of complications with it as well. Being concussed and the danger also of having bone fragments enter the cranial vault.

It is debatable how far a sword strike like this can really penetrate. There are also many variables such as sword geometry and construction quality. I do not think that matters so much as the art we study is long outdated and such variables only cloud important points. The arguments can indeed become endless.

These are unpleasant things to think about. We should, however, realize the very important aspect of angles and proper power and control of the sword.

This is based on my own knowledge and what I have learned over the years practicing both sword and massage therapy. It is not based on any clinical or hard evidence of sword fighting. I want to expand the thinking and root of some of the ideas in what I consider a common-sense approach to sword combat and anatomy and physiology.

©2018 S.F.Radzikowski

ラジカスキー真照

館長Saneteru Radzikowski is the head sword instructor of Shinkan-ryū Kenpō. He lives and teaches Iaijutsu and Kenjutsu from Nara, Japan.

Making Excuses In Martial Arts

In the dojo, when I hear a student offer excuses to a teacher, I can...

Budo Don’t

Don’t be in love with your weapon. Don’t be in love with your uniform. Don’t...

Fear Isolation Martial Arts

Budo does not begin and end when you pass through the dojo, or step on...

Greed And Martial Arts

We must endeavor to cultivate generosity while looking at the roots of our greed. Removing...

Martial Arts and The Path: Strive for the truth

If you study the way and path 道, then you should understand the truth correctly....

Jealous Martial Artists

Martial artists should be aware of what can live in the shadow of righteousness; jealousy...

Honesty and the Martial Arts Hermit. Being a good budō teacher and student.

When people want to find a martial arts teacher, do they often think of mister...

Kata: Classical Japanese Samurai Training Method

Bujutsu Kata Training in martial arts can be done in different ways. One of the...

Happy New Year

From all of us at Shinkan-ryū Kenpō to you, Have a wonderful New Year Celebration....

Budō Practice Is Everywhere

Practicing without many excuses not to is a good practice.

Are Combat Skill, Self Defense & Martial Art The Same?

Why make the distinction between martial art and combat skill? I believe that combat skills...

What does Bugei mean?

Bugei translates as Martial art, Military arts, or Arts of war. Bu 武 means warrior...

Code of Bushido Righteous Heart

Being righteous and doing the right thing is one of the foundations of body and...

Is Studying Multiple Martial Arts Ok?

Many people study more than one martial art. There can be varied reasons, such as...

Bujutsu Truth

Be honest. Move with the truth and discard the lies and false facades. Leave them...

What is Koryū?

Japanese martial arts are usually defined in two groups. Pre-modern and modern. There are no...

Cómo aprender Kenjutsu?

Aprender cualquier cosa tan profunda como un arte marcial requiere de un maestro. El kenjutsu,...

A Disease of the Swordsman

The Sword and its study. Hesitation (doubt) is one of the four diseases in swordsmanship....

The End of Training & Boredom In Martial Arts

Budō Is Limitless When does training end? When do we become a master? The short...

Budō Practice & Sacrifice

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent="no" hundred_percent_height="no" hundred_percent_height_scroll="no" hundred_percent_height_center_content="yes" equal_height_columns="no" menu_anchor="" hide_on_mobile="small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility" status="published" publish_date="" class="" id="" background_color="" background_image="" background_position="center...

How to learn kenjutsu?

How to learn kenjutsu? Learning anything as profound as a martial art needs a teacher....

Wisdom Martial Arts Keiko & Buddhism

For those that lack wisdom the way is difficult. It is best to consider the...